Budget 2024 Key Points: From the govt’s fiscal deficit to allocations for health and education to GDP growth, here’s what the Interim Budget 2024 reveals.

Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman Thursday presented the Union Budget for the next financial year (2024-25). It was her sixth budget presentation, but was different from all the others because this was an interim budget.

As such, it was natural for the FM to spend more time recapping the achievements of the two back-to-back governments under Prime Minister Narendra Modi over the past decade than announcing major new initiatives. Here are some of the main takeaways from the interim Budget of 2024-25.

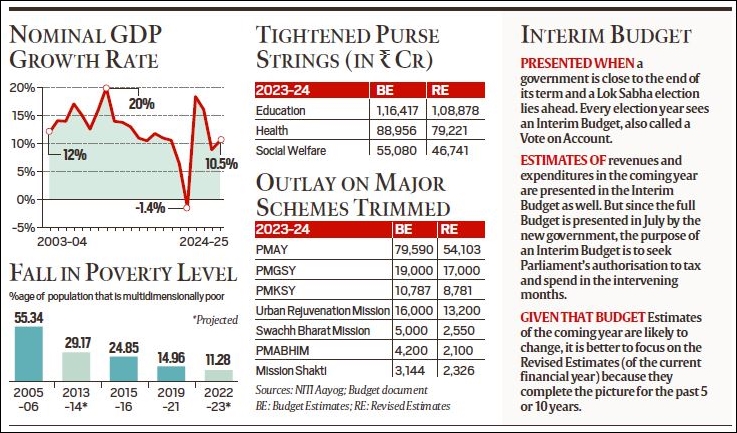

Muted outlook on GDP growth

The nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the size of the Indian economy in terms of today’s prices. This number when divided by the rupee-dollar exchange rate gives India’s GDP in trillions of dollars. The nominal GDP is the actual observed value.

Reduction in fiscal deficit

Fiscal deficit essentially shows the amount of money that the government borrows from the market. It does so to bridge the gap between its expenses and income. Fiscal deficit is the most-watched variable, because if a government borrows more, it leaves a smaller pool of money for the private sector to borrow from. That, in turn, leads to higher interest rates, thus disincentivising borrowings by the private sector and further dragging down economic activity in the form of lower consumption and production.

If the government tries to print more money instead of borrowing from the market, that too leads to negative effects such as inflation, thanks to a sudden surge of additional money chasing the same supply of goods and services.

Moreover, each year’s fiscal deficit adds to the pool of government debt. If fiscal deficits continue to grow unrestrained — that is, if a government continues to live on borrowed money — repaying the debt and associated annual interest payments tends to become a critical concern. Retiring old debt eventually requires governments to tax its citizens, which, again, drags down economic activity.

It is for this reason that the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act of 2003 requires the Union government to contain its fiscal deficit to just 3% of the nominal GDP. However, barring 2007-08, India has never met this target.

The deficit had worsened in the wake of the Covid pandemic — shot up to 9.2% of GDP — but since then the government has been able to bring it down each year. In the current year, the government had set a target of 5.9% and revised estimates show it is likely to be even lower at 5.8%. Further, the FM has announced similarly ambitious targets for FY25 — at 5.1% of GDP— and FY26 — at 4.5% of GDP.

This is a welcome achievement because it is likely to bring down the cost of borrowing for the private sector. However, it leads to two key questions: how is this fiscal consolidation being achieved, and what will be its impact on growth.

Capex target not met

All government expenditure can be divided into two broad categories: revenue (to meet daily needs such as fuel bills, salaries, etc.) and capital (making productive assets such as roads, schools, bridges, ports, etc.). There is a clear advantage for the broader economy when the government ramps up capex. Every Rs 100 spent on capex leads to a Rs 250 increase in GDP. Revenue expenditure, on the other hand, returns less than Rs 100.

The cornerstone of the Modi government’s last few budgets has been a concerted push to raise capital expenditure. In fact, the highlight of Budget 2023-24, presented last February, was the announcement that government capex would be Rs 10 lakh crore — more than double the Rs 4.39 lakh crore of 2020-21. For this, the FM had received a lot of praise.

However, revised estimates show that this capex target was not met in the current year — it stands at Rs 9.5 lakh crore. This explains some part of the reduction in fiscal deficit as well as raises some concerns about the likely impact on the overall growth momentum to the economy.

Health, education spends cut

The story of cut-backs continues when one looks at some of the key ministries and departments.

Health and education are two key areas for any developing economy. No economy has developed without first investing in improving the health and education of its population. Historically, in India, budget allocations towards health and education have been lower than required. To be sure, most years, health and education allocations range between 2.5% to 1.5% of the total government expenditure.

However, the revised estimates show that even those targets have not been met in the current financial year.

For instance, the government was supposed to spend Rs 1,16,417 crore on education but ended up spending Rs 1,08,878 crore.

Similarly on health, it budgeted an expenditure for Rs 88,956 crore but actually spent only Rs 79,221 crore.

Cuts in core schemes

If one looks at some of the most important government schemes across different ministries, the story of cut-backs in expenditure plays out.

For instance, revised estimates for the outlays on major schemes show that most of the so-called “core of core schemes” meant for the most disadvantaged sections of society, such as SCs, STs and minorities, have witnessed cuts.

For instance, the Revised Estimates (RE) for the Umbrella Scheme for Development of Schedule Castes are Rs 6,780 crore against the Budget Estimates (BE) of Rs 9,409 crore.

For STs, the RE is Rs 3,286 crore against a BE of Rs 4,295 crore.

For minorities, the fall has been the sharpest. In 2022-23, budget estimates pegged the expenditure at Rs 1,810 crore. As it turns out, that year the government actually spent Rs 233 crore — just 13% of the budgeted amount. In the current year, the BE was Rs 610 crore but the RE is just Rs 555 crore.

For the Umbrella Programme for Development of Other Vulnerable Groups, the RE is Rs 1,918 crore, down from a BE of Rs 2,194 crore.

I-T is biggest income generator

Traditionally, the biggest chunk in the government’s financial resources comes from market borrowings. Among the genuine income generators, it is the indirect taxes and the corporate tax that provide the most money. But budget estimates for the next financial years show that income tax collections will be the top contributor (after borrowings).

The Budget documents suggest that income tax revenues will account for 19% of all government resources in FY25. Corporate tax will account for 17%, GST for 18% and borrowings for 28%.